1789

September 9 – October 15

More than 130 years ago in his Principles of Psychology, William James asked how many things we can attend at once. His early psychology reflections start with himself, like many philosophers before him in modern history. He speculates in first person. He says: “My experience is what I agree to attend to. Only those items which I notice shape my mind—without selective interest, experience is an utter chaos.” With some surprise for me, James vaguely concludes, or rather poses, that “the number of things we may attend to is altogether indefinite, depending on the power of the individual intellect, on the form of the apprehension, and on what the things are.” In respect to Andrea Romano’s exhibition 1789, I do believe I can attend to a rather finite number of things, yet this need not be a counterexample to anything James proposes. I do attend to at least two things in each of these artworks, but there might be more, perhaps even an indefinite amount, as he says. I ultimately agree with him.

The title of this show cued me in: 1789 is obviously the year where the French revolutionised things such as the nation-state, but also the code to open Andrea Romano’s gallery door in its previous Parisian location, as he explains to me—for those unfamiliar with the French capital, lots of buildings here can be accessed with smartphone-like four-digit pin codes. My mind takes possession of one object, the number 1789, where two trains of thought simultaneously pull over: the year and the code. I lean towards either of them, bending my brain left and right, until the number 1789 becomes one thing more than another. I wish I could still use metaphors such as “shades of grey” here to describe where these objects belong…

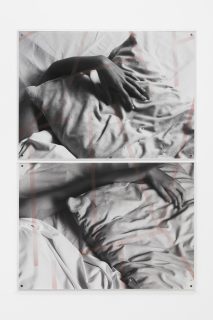

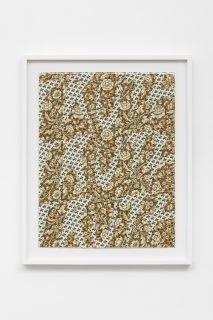

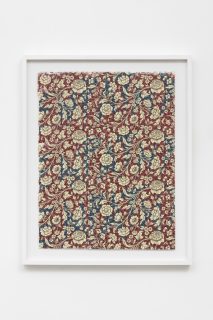

Take an artwork in 1789—the show, not the year, not the building—like Simple Prepositions, Mother Mold (1). It’s layered like 1789 itself. Andrea Romano has created a single object, one made of paper, ink, magnets, etc., in which I attend to both an image of hands laying on some garment and floating letters. The layers blend with one another so I need to push my brain hard to lean on one at a time. What are those objects within an object? I learn from him that the letters on the picture form the word “ineffable.” I learn that the picture is a picture of one of his performances from some time ago. Similarly abstract words appear in most of the works in the show: “deference”, “captivity,” “immanence.” In 1789, I am able to attend to two things at once for a second time too: a different body of work in which Andrea Romano uses textured paper typically covering the bottom of drawers, here utilized as a color-blind test displaying abstract concepts in writing. I see the patterns, the flowers, the repeating motifs, yet I read words: “empathy,” “truth,” and “Schadenfreude.”

William James quotes different theories about the amount of things we can think and do at the same time. One of them says that “the most favorable condition for the doubling of the mind is its simultaneous [sic] application to two easy and heterogeneous operations. Two operations of the same sort, two multiplications, two recitations, or the reciting one poem and writing another, render the process more uncertain and difficult.” However difficult it is to grasp two postures in each of Andrea Romano’s works, it is not as uncomfortable, or even nearly as nightmarish as asking anyone to write and recite two different poems at once. Does it follow that the things to which I attend in each of his works are neighbouring after all?

The private and public, his and ours, these are the typical factions cooperating in the compacted artworks of 1789. A revolution and the artist’s gallery, his pictures and abstract concepts, his personal pieces and common values: I am taken sideways, ambiguously, through what Andrea Romano chose to show me, packed in one object and framed on the walls. A recent text by him, published in a famous art magazine, [1] makes me uncomfortable with his revealing of very private memories. Yet, in a blink of an eye, I can move on, focusing on the paragraphs right below, which present historical facts about fascism, and more. He serves me this mix in a single letter. There is something demanding, slightly violent. My mind doubles, like it does in front of his works in 1789, until it comes back together with fair aesthetic pleasure.

[1] “Letter from the city” by Andrea Romano, published in FlashArt Italia 353, Summer 2021.

PIERO BISELLO

August 2021